I introduced the Projection Canvas as a tool for founders to give useful input into their financial projections. For me, ‘useful’ means a level of detail that is not too much and not too little.

The goal of early stage projections is to tell a financial story that fits the company’s overall strategy.

One pitfall common to fancy tools and Excel models is giving founders a feeling they can predict the future. Predictability is something you can only earn through experimentation and running the business.

At the beginning it’s more important to lean into what you do not know. The Projection Canvas highlights the important parts of the story without adding needlessly distracting details.

Let’s see it in action.

Example 1 - Software startup

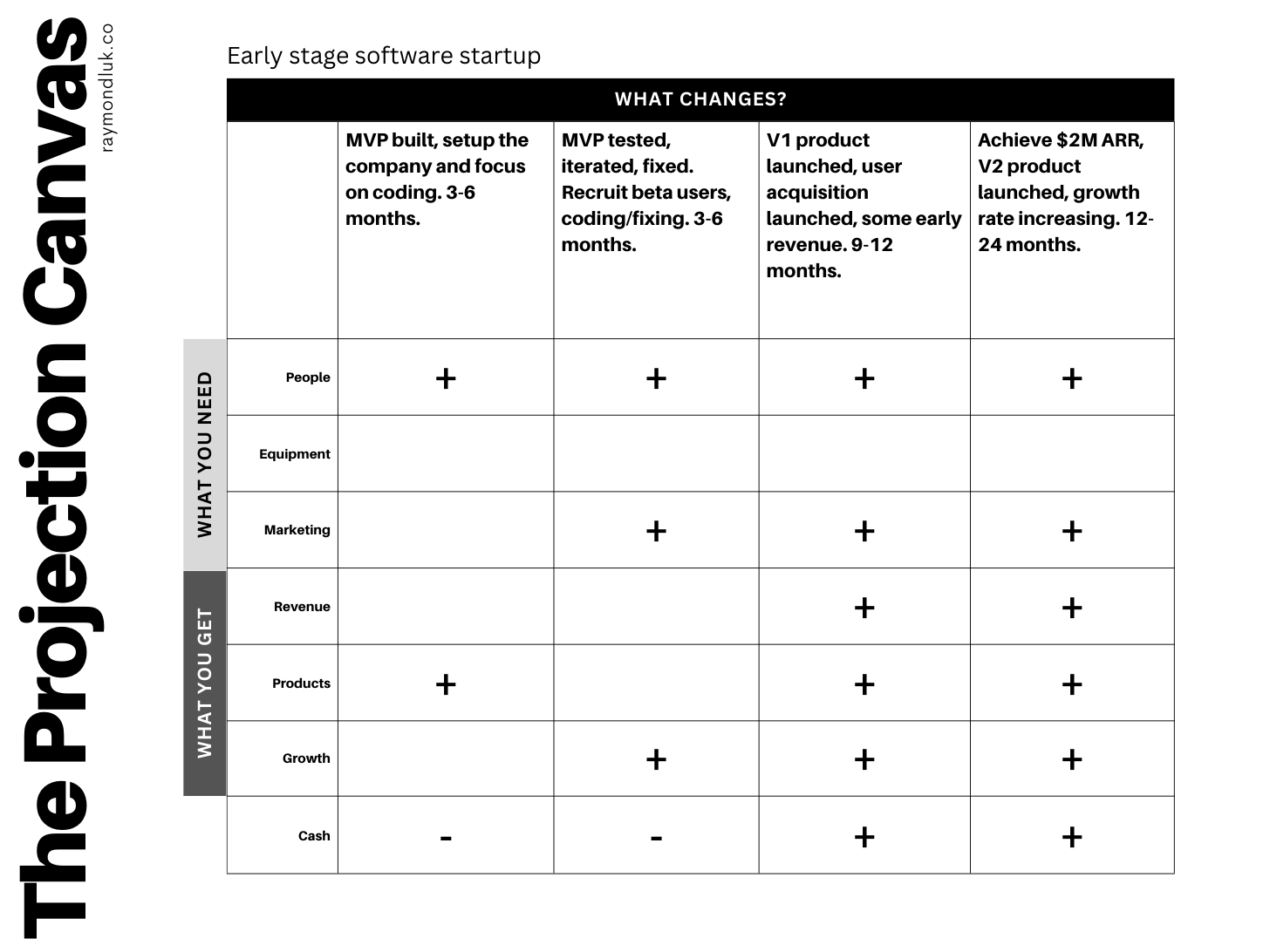

This is an example of what a first iteration of a Projection Canvas could look like for a typical software startup. Even without any details you can see the outline of a story being told: this is a lean startup that hopes to get to traction early; the first version of the product can be built right away:

Four stages have been identified, each with a range of months it could take to complete.

The cash line shows losses at the beginning because there is no revenue. This startup will need to fund that somehow, but that can be worked out later.

Here is the next iteration of the canvas with details filled in. Only what changes from stage to stage has been added, keeping things clean and focused.

Avoid the temptation to add too much to the Projection Canvas. This shouldn’t be a to-do list or a place to record every single prediction. The small size of each box should be a hint. Ask yourself: does this additional detail have a big impact? If not, leave it out.

There are only four types of numbers on this canvas: average salaries, high-level marketing spend, projected user growth and revenue growth.

For a software startup the place to focus attention, debate and to validate is probably in the user and revenue growth numbers.

The completed canvas tells a complete story of how this startup sees the future.

What it looks like as a spreadsheet

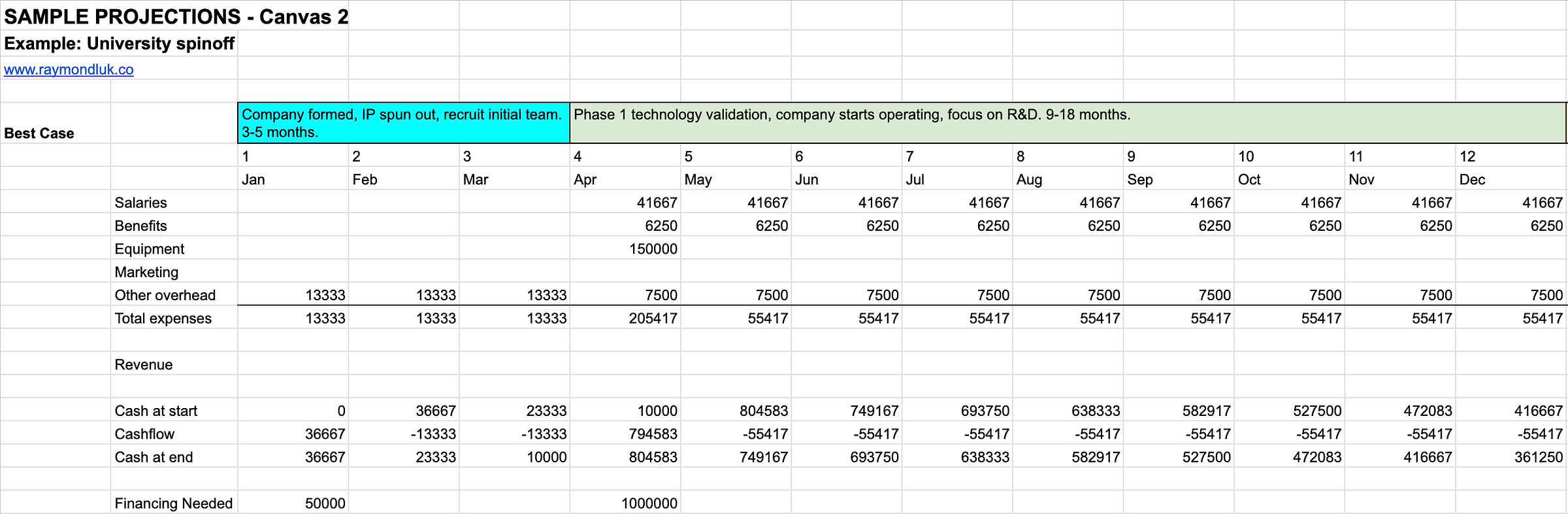

I extrapolated the canvas into a simple spreadsheet and created best case and worst case versions. I’ve shown the first 12 months below but you can access the full spreadsheet here.

This is a very simple spreadsheet. It does not accrue revenue or expenses. There are no provisions for income tax or liabilities. I even put revenue below expenses.

Later, you may need more complex market sizing spreadsheets and a granular model for your unit economics.

But none of those details matter at this stage of financial projections. The goal here is financial strategy and storytelling, not budgeting or calculating depreciation. Without a grasp of the big picture all the little details create a weak scaffolding for your financial story.

I made the spreadsheet purposefully simple to show how few details you need to understand and tell your story.

A word about calculating how much financing you need

If you zero out the “financing needed” line, you’ll see negative numbers in the “Cash at end” line, i.e. your bank account. This isn’t a tool to automatically calculate how much capital you need to raise, and when.

But you can (and should) play around with inputting enough financing so your ending cash is always positive. Understanding this relationship is the key to mastering fundraising.

Example 2 - University spinoff

In my second example, I chose a very different type of startup, one that’s formed from University IP that’s spun off. This fictional deep tech company has a different growth profile and capital needs.

Again, from just the first iteration of the Project Canvas you can deduce that this is an R&D-heavy company with a slower commercialization plan:

In reality the cash line cannot be negative in all four stages. But it’s a good idea to leave the financing strategy for later. For now, this company needs cash for equipment and R&D up until phase 4 when commercialization begins.

This startup has a higher level of expenditures overall. Salaries for technical specialists are higher, there’s a need for equipment and more time passes before they earn first revenue.

But again, there isn’t a lot of value to adding much more detail to this canvas. I use average salaries because at this stage, predicting future compensation of individuals is not worth the time. Or someone else could do it better than you could.

Imagine a VC asking how you intend to spend your seed round. This canvas would have all the answers you need.

The spreadsheet

In the spreadsheet, the worst case scenario is a full 16 months slower. You can see the full spreadsheet here.

Comparing the two scenarios, you’ll notice the worst case takes 16 months longer and requires another million dollars in capital. That’s actually not too bad an outcome if you arrived at the same stage of development.

That’s because I assumed that expenses would stay steady but not go up significantly if a stage took longer to complete.

In the real world things don’t always work that way. Struggling companies often reach for new spending to solve problems that might just require staying the course.

Splitting things into phases and working with this simplified spreadsheet should give founders a better way to think about that decision.

The reality is that you don’t know how long each stage will take. A good financial plan takes that into account.

Wrapping things up

Between the Projection Canvas template and the spreadsheets, this should give founders enough to try it on their own. This is useful for anyone putting together a pitch deck for their raise. But it’s useful for any planning process at any stage especially when you want to capture diverse input.

If you end up applying this to your startup please reach out to me and let me know. I’d love to see examples and learn what works or what doesn’t.