What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

Part 8 in a series on ownership

This is part of a series on ownership for founders. This isn’t a series on how to raise, but how to understand different owner perspectives, including your own.

When investors have to chase deals they call the market ‘frothy’.

When the situation reverses, founders call VC terms ‘punitive’.

It’s a tough fundraising environment right now in 2023 but it’s inaccurate to say it’s “investor friendly.” The higher risk in the market affects both investors and founders.

That can lead to confusion on the part of founders as they face falling valuations, down rounds and bridge rounds, changing deal terms and different exit possibilities.

No one wants to think about what could go wrong in their startup. But it’s essential to understand how in order to navigate the path forward.

Down Rounds

A down round is a fundraising event where the (pre-money) valuation is below the previous round’s (post-money) valuation. A flat round, where the valuation stays the same, is essentially a down round due to the time value of money.

Almost 20% of funding rounds in 2023 have been down rounds according to Carta. This is not good news for startups but it should help de-stigmatize down rounds for founders: you’re not the only one!

The fact that the market wants to re-price your shares should not be a surprising phenomenon. Things happen in the market environment that are out of your control (these days, take your pick.).

Also, the other side of your “change the world” disruptive story is the inherent risk that entails. Innovation is unpredictable, which creates both the opportunity and the need to constantly re-adjust.

Take Loom’s recent exit to Atlassian for $975M in cash.

That was a down round.

The Series C was raised at a $1.5B valuation but the final sale was done 35% less than that.

Founders and employees still netted $400M so no one thinks of this exit as anything but an amazing success

A16z’s 1x liquidation preference saved them from losing money on their investment. They still lost in the sense that their returned capital did not earn anything during that time. But it doesn’t seem unfair because the company raised on a $1.5B valuation only to sell 35% less in a short time.

So not all down rounds are bad, and not all investor-friendly terms are unfair.

Bridge Rounds

A bridge round is when a startup needs more money to reach its next milestone but isn’t ready, or able, to raise a completely new round.

There are many legitimate reasons why companies need to bridge, external and internal. Or you could just be executing really poorly. Believe me, investors will spend time trying to determine which case applies to you.

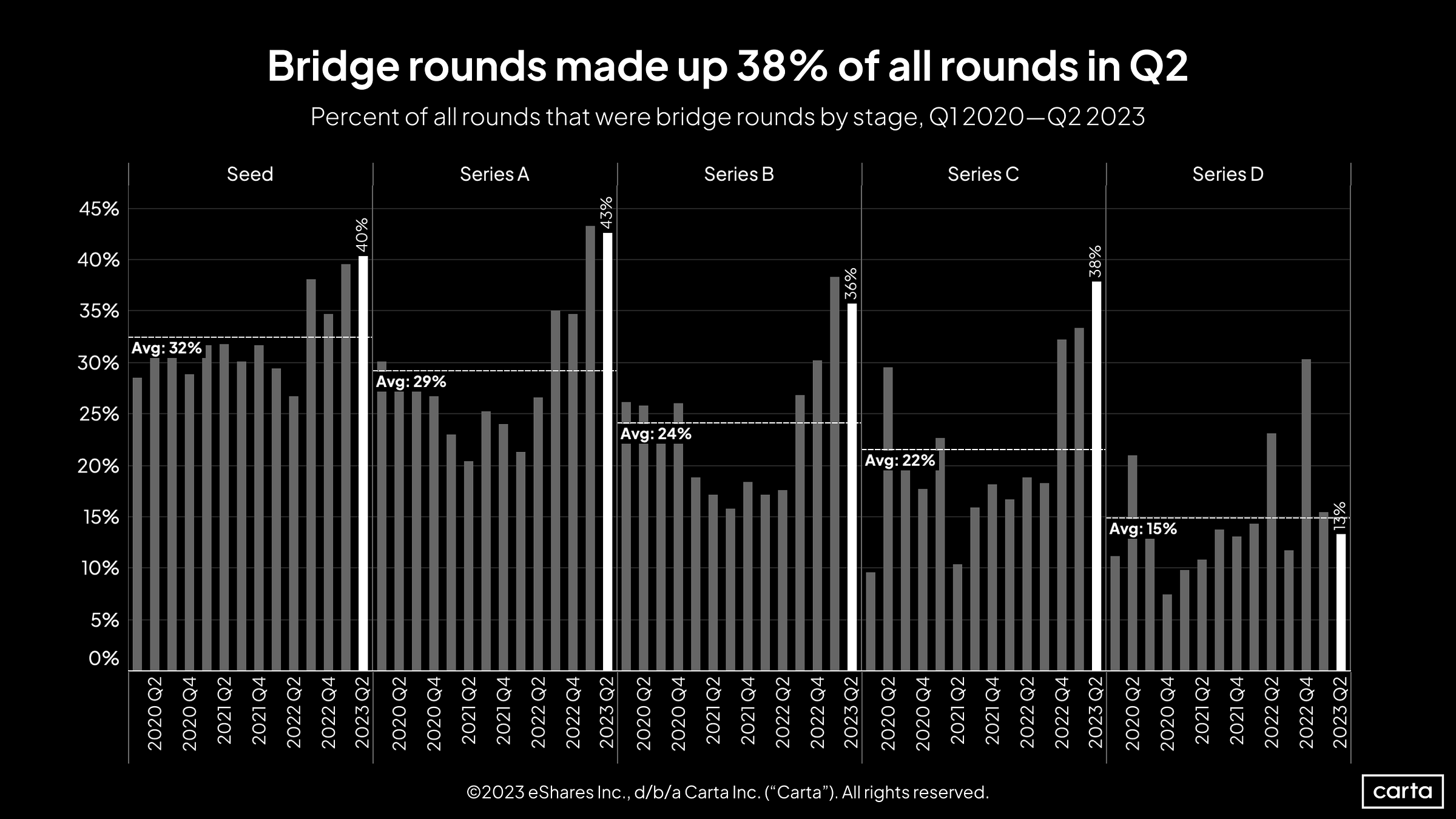

Like down rounds, bridge rounds have grown significantly, up to 38% of all rounds in Q2 2023.

This obviously reflects the longer time periods between rounds due to the higher bar required to raise the next round. More time equals the need for more money.

For early stage startups who already have raised Safes, beware the dilution of stacked post-money Safes. As I explained in my post on cap tables, each post-money Safe has built-in anti-dilution. The more you raise the more shares that investor is entitled to so they maintain whatever % ownership was promised in the post-money cap.

When you think about it, every company is a bridge to some future milestone. So reducing burn and gunning for profitability is also a good way to bridge.

Deal Terms

The pendulum has swung back to VCs and tougher deal terms are back.

Scott Hartley from Everywhere Ventures wrote about it recently in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Terms. Pitchbook also covered some of the “cap table chaos” out there in Investor-friendly terms rankle startups’ early backers.

Here are some of those terms broken out into whether they focus on more control, or protecting downside or upside.

Control

More categories of vetos

Lower spending thresholds before requiring board approval

More board seats

Downside protection

1x liquidation preferences (very few deals without this)

Anti-dilution (including capped, post-money Safes)

Higher interest rate on convertible notes

Cumulative dividends

Upside protection

Lower valuations

Multiple liquidation preferences (2x, 3x)

Pay to play

Note that these are not only investor friendly but new investor friendly. They can require concessions not only from founders but from previous investors especially if they don’t re-invest or have anti-dilution protection.

Early Exits, Slower Growth

I wouldn’t necessarily say that selling early or growing more slowly is ‘wrong’. But they are definitely bad outcomes from the perspective of the VC who foregoes a return that will move the needle for their fund.

An openness to selling earlier for a lower valuation may be the optimal outcome for many startups in this environment. Well, unless the value is so low an investor with a liquidation preference gets all of the proceeds.

In a tough market, any exit is better than none. The product, IP and people live to fight another day.

Of course another option is to get off the venture path altogether, grow more slowly but hit profitability faster. This is not an easy change to make because your cap table probably has funds who need to get their money out vs an exit, not a stream of dividends.

But startups who are able to reduce burn and focus on profitability have both options: never to have to raise (but setup a tough negotiation with existing investors) or go back to the market later in a much stronger position (minus the hyper growth).

The Bottom Line

In an uncertain market there are a few things founders can do to chart the best course.

Think about your payout

Very few founders ever think about the potential payout of their ownership in their startup. It’s so far in the future and you aren’t building a company just to make money right?

But using a simple (well, fairly simple) tool like a decision tree to map out the future can be incredibly useful. No, it does not help you predict the future.

But it does something more useful: it creates a mindset where you accept that there are multiple paths and possibilities, each with their own probabilities of success or failure.

Thinking about what could go wrong allows you to better understand that although you should always negotiate for the best deal, both you and your investors need to build in mechanism and protections for when thing happen unpredictably.

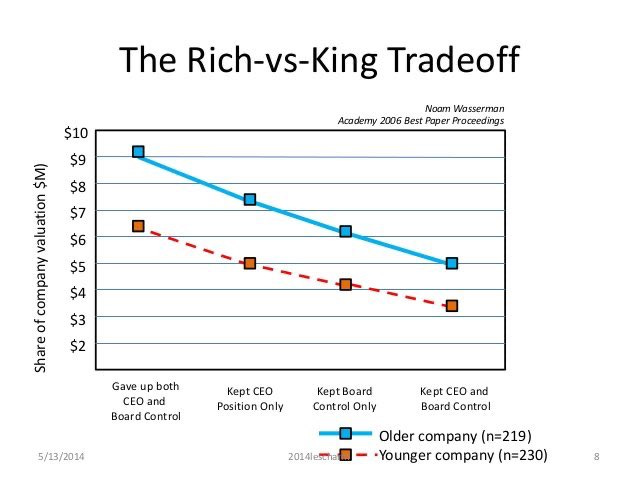

Do you want to be Rich or a King?

One of the most uncomfortable conclusions from The Founder’s Dilemmas (Wasserman) is this: founders who had the most control had the least financial return. I haven’t seen an update on this, which was published in 2006, but I can see no reason why it would have changed.

This doesn’t mean you should find every reason to give up control, i.e. do not try this:

VC: I want 3 out of 5 board seats

You: Hell, you can take all 5!

VC: 🙄

You need to question your assumption that each piece of control you give up somehow hurts your ability to get what you want. The data says otherwise. That means you should try for the best terms but maybe not die on that hill.

Stop worrying about style points

In startups there is always this undercurrent that there’s a “right” way to do it. The right pace, the right amount of funding at the right time, and with the right investors of course.

Tougher times, like the one we’re in now, force those assumptions into the light where they can be debunked.

Whether you’re having difficulty raising money or contemplating a down round, keep your focus on building your company, not fitting into some fictional mold.

I recently came across Braid, a fintech startup that closed in September 2023. The founder, Amanda Peyton, wrote a courageous and thoughtful debrief which I highly recommend founders read. By the way, I think she is overly harsh on herself. So many things that look like mistakes are only that in the perfect light of hindsight.

Amanda talks about getting the timing wrong by waiting too long to raise money, then not being able to when she felt the time was right:

I called one of our investors in early October 2021 to report that we’d figured it out, that it was going to work. He said, “great, raise money immediately, the time is now.” This advice was excellent, prescient, and correct.

I fought him. I said, “if our numbers are great and consistent, we can always raise, let’s wait it out a few more months.” I believed this, too.

- Amanda Peyton, Braid

The game of company building, especially startups, is unpredictable. It’s not only impossible to be predictable but it’s not even the desired goal. We would have so much less innovation if we merely achieved what we set out to do.

Things going wrong are not negative signals for some future VC. They are part of being a founder and part of the whole concept of ownership.

I can’t second guess Amanda’s decision to delay fundraising. But when she says “Every dollar a startup can raise is a gift. For a time I lost sight of this” I think what’s she’s saying is she briefly lost sight of what could go wrong.

It’s never the part that founders like talking about but it’s built into the game we’re playing.